Dealing With Money in Software

Some time ago I was teaching my kid about money, as an extra activity on top of his homework. He has some savings in a little safe box and we decided to count how much he had accumulated so far. We took the coins out and started counting them, one by one. 10¢, 20¢, … 80¢, 90¢, 1$. “One?”, he asked, “but we are about to count to a hundred, why one now?”. I didn’t expect that. What I took for granted all this time came as a realization that money is not like the other numbers. It’s a sub-class of numbers with special rules.

On the spur of the moment, we could tell that’s just a matter of scale, but this is not the case. Comparing to the metric system, we can have a table that measures 100cm x 150cm or 1m x 1,5m. In athletics 1500m is a middle-distance, not 1.5km. I’m 1.80m tall, but my fitness app asked me to put 180cm in the registration form. In money, cents range from 0 to 99¢. Nobody has 230¢ cents in their pockets. They have 2 dollars and 30 cents instead. Any value greater than 99¢ is in dollars, sometimes followed by fractions in cents. These rules are applicable for the majority of currencies around the world.

In the universe of money, arithmetic is not fully useful. Consider this simple scenario: you have 100$ and you want to fairly split it with 3 people. So, you divide 100 by 3 and get 33.3333333… but concretely, money can only represent 33.33. If you multiply 33.33 by 3 you get 99.99, which means you still have 1¢ to give. As you can see, money can be split. It isn’t a good idea to divide it.

The accumulation of rounding issues may have an important impact over time, specially when using computers, which are capable of processing millions of operations per second. It can represent millions in gains or loss for the involved parties, thus programmers must be careful when dealing with money in their applications.

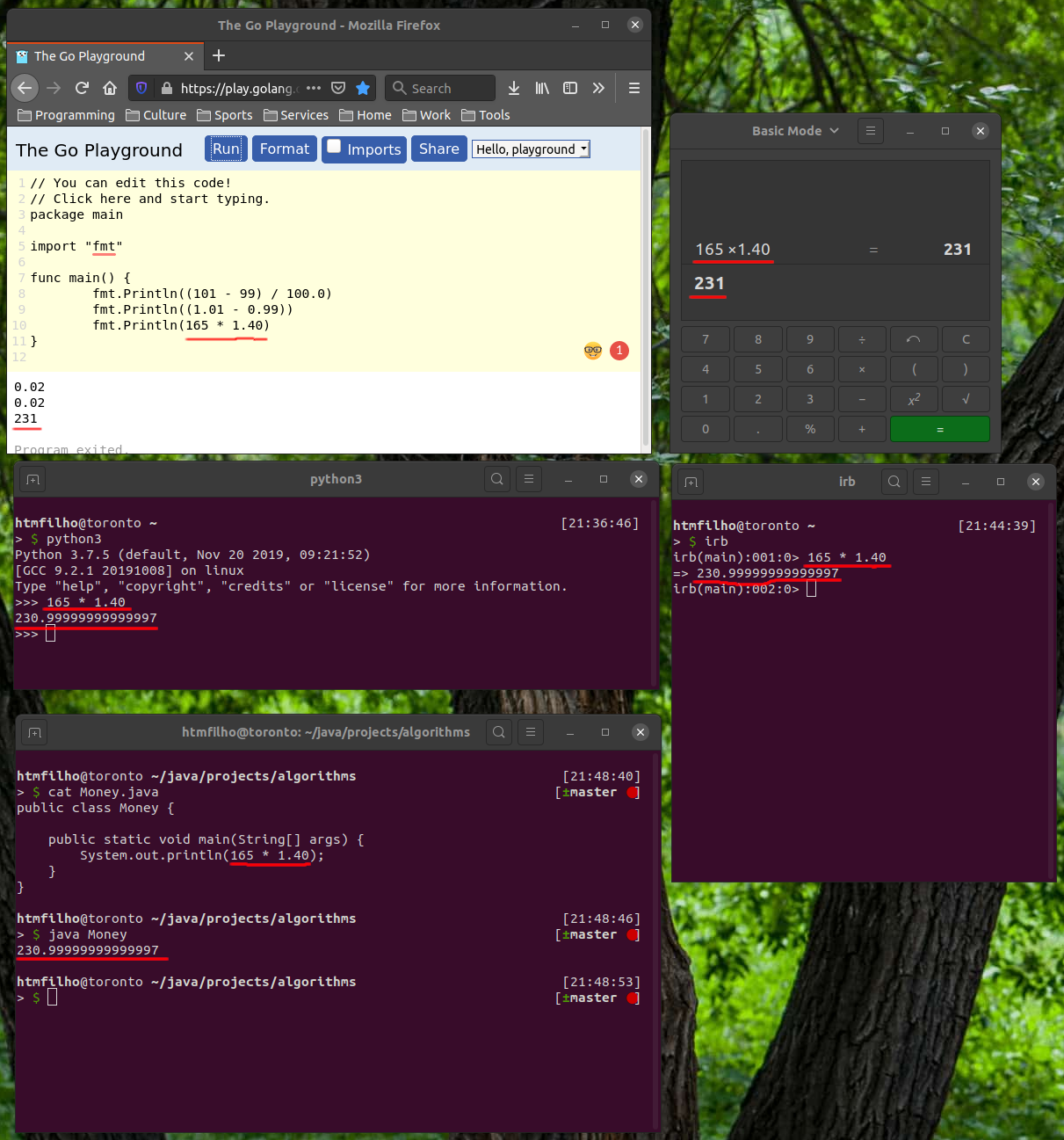

Care starts right at the basics. When looking at the characteristics of monetary values, it is tempting to use a primitive type with support for decimal places, such as float or double, but they can’t be accurately represented by 0s and 1s (binary). For example, 5000000.02 - 5000000.01 is 0.009…, not 0.01; 165 * 1.40 is 230.9999… not 231. I run to my computer and played with these examples in several programming languages (Java, Python, Ruby, and Go), trying to find one with a different behavior. Curiously, Go behaved like a calculator, working well with float32 without the above problems (however, the usual issues happen with float64).

The reason why Go behaves well above is because numbers with decimal places are float32 by default, while in other languages they are float64 or double. By forcing Java to use float32, we get the same result: 165 * 1.40f == 231.

I was happy with Go float32 until I run an example found in the book Code Complete 2nd Ed., page 295:

// false

1.0 == (0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1)

// true

1.0 == (0.1 * 10)

A large proportion of the computers in this world manipulate money, but no modern programming language implements a primitive type to properly support it. The problem with money is that it is not just about arithmetic operations. It is also about currency, conversions, indexes, formatting, etc. This is a complex type, as recognized by the Java community when they proposed the spec JSR 354. Python also has its money library, as well as other languages.

In case a good abstraction of money is not available, the book Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, page 488, offers the requirements to implement a basic one. In summary:

-

A value is attached to a currency to give context. Without a context, it is risky to compare two values. For example: 1 CAD != 1 EUR but 20 CAD == 20 CAD.

-

A value may have 3 decimal places to minimize rounding differences and to support a larger variety of currencies would wide. But, as remarked by @koblas, if the currency works with 2 decimal places, do not consider the third place in any calculation, setting it with zero all the time.

-

The way we represent money is not necessarily the way we show it. We may store 3 decimal places but we may keep the third one hidden. Optionally we can show the symbol of the currency.

-

The arithmetic operations are encapsulated to deal with the particularities we have discussed so far.

Back to the numeric representation, a popular technique to achieve precision with monetary values is to work with 64-bit integers. It is big enough to work with 3 decimal digits. To illustrate, let’s represent the amount 84598.47 as an integer, with a combination of division and remainder:

84598.47 -> 84598470

84598470 / 1000 = 84598

84598470 % 1000 = 470

(84598470 % 1000) / 10 = 47

84598470 / 1000 +"."+ (84598470 % 1000) / 10 -> "84598.47"

As you can see, this technique is verbose. It requires encapsulation to implement arithmetic operations, comparisons, and presentation. But it works to the point of preventing us from using float or double. The most pragmatic approach is still using an existing library, instead of implementing it ourselves.

To conclude, let’s play a bit with an algorithm to split money as fairly as possible in Go:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

parties := split(100, 3)

fmt.Printf("split 100 with 3: %v\n", parties)

parties = split(67, 4)

fmt.Printf("split 67 with 4: %v", parties)

}

func split(amount, n int) []int {

division := amount / n

toDistribute := amount - (division * n)

parties := make([]int, n)

for i := 0 ; i < n ; i++ {

parties[i] = division

}

j := 0

for i := toDistribute; i > 0 ; i-- {

parties[j] += 1

j++

}

return parties

}Output:

split 100 with 3: [34 33 33]

split 67 with 4: [17 17 17 16]

Recent Posts

Can We Trust Marathon Pacers?

Introducing LibRunner

Clojure Books in the Toronto Public Library

Once Upon a Time in Russia

FHIR: A Standard For Healthcare Data Interoperability

First Release of CSVSource

Astonishing Carl Sagan's Predictions Published in 1995

Making a Configurable Go App

Dealing With Pressure Outside of the Workplace

Reacting to File Changes Using the Observer Design Pattern in Go

Provisioning Azure Functions Using Terraform

Taking Advantage of the Adapter Design Pattern

Applying The Adapter Design Pattern To Decouple Libraries From Go Apps

Using Goroutines to Search Prices in Parallel

Applying the Strategy Pattern to Get Prices from Different Sources in Go