Interesting Behavior of the EJB Timer Service

In a recent discussion in the CEJUG technical discussion list, we figured out an interesting behavior of the EJB Timer Service that is very important to know when implementing a time service.

First, let me contextualize EJB Timer Service and some situations where it could be useful. EJB Time Service is an interesting feature of the EJB Specification that allows routines to be executed in a certain time (24 hours from now or 01/04/2010 at 23:35) or in a certain frequency of time (every 12 hours or every day at 02:00). The schedule of routines is very appropriate to perform automatic maintenance tasks such as cleaning temporary data, generating complex reports, sending alert messages, etc. Timers are also useful to efficiently use computational resources when systems are in idle mode. A system architect should have a good understanding of this feature to optimize the implementation of corporate solutions, where a lot of data are processed in batch. You can learn more about EJB Timer Service in the book EJB 3 in Action.

To understand this particular behavior, consider a routine scheduled to execute every 2 hours. What would happen with the next scheduled execution if the routine spends more than 2 hours to finish? It’s important to estimate well the interval between executions to avoid situations like this. However, if for some reason the routine didn’t finish its execution before the next schedule, then it is important to understand the consequences of this scenario.

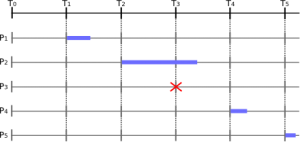

We could observe that, if the current execution lasts longer than the configured interval, then the next execution won’t happen. The schedule will be back to normal only when the current execution finishes. The figure below illustrates this behavior.

The timer process P3 was expected to execute at T3, but it didn’t because P2 execution hadn’t finish yet. However, P2 finishes before T4, then P4 is still expected to run on time. The stateless session bean bellow simulates this behavior:

@Stateless

public class ImageBsn implements ImageLocal {

@Resource

TimerService timerService;

public void init() {

timerService.createTimer(60 * 1000, 60 * 1000, null);

}

@Timeout

public void cleanUnusedLocations(Timer timer) {

Calendar now = Calendar.getInstance();

Calendar later = Calendar.getInstance();

System.out.print("Cleaning at "+ now.getTime());

later.set(Calendar.MINUTE, now.get(Calendar.MINUTE) + 3);

while(now.get(Calendar.MINUTE) < later.get(Calendar.MINUTE)) {

now = Calendar.getInstance();

}

System.out.println(" and Cleaned at " + now.getTime());

}

}The code above schedules the timer to execute the timeout method every 60 seconds. Then the timeout method has a routine that keeps it running for more than 2 minutes, forcing the timer to postpone some scheduled executions. The output is:

INFO: Cleaning at Thu Mar 11 17:48:39 CET 2010

INFO: and Cleaned at Thu Mar 11 17:51:00 CET 2010

INFO: Cleaning at Thu Mar 11 17:51:39 CET 2010

INFO: and Cleaned at Thu Mar 11 17:54:00 CET 2010

INFO: Cleaning at Thu Mar 11 17:54:39 CET 2010

INFO: and Cleaned at Thu Mar 11 17:57:00 CET 2010

Therefore, you don’t have to worry about implementing a multi-thread safe code in the timeout method, but you should evaluate the consequences of having one of the executions canceled.

Recent Posts

Can We Trust Marathon Pacers?

Introducing LibRunner

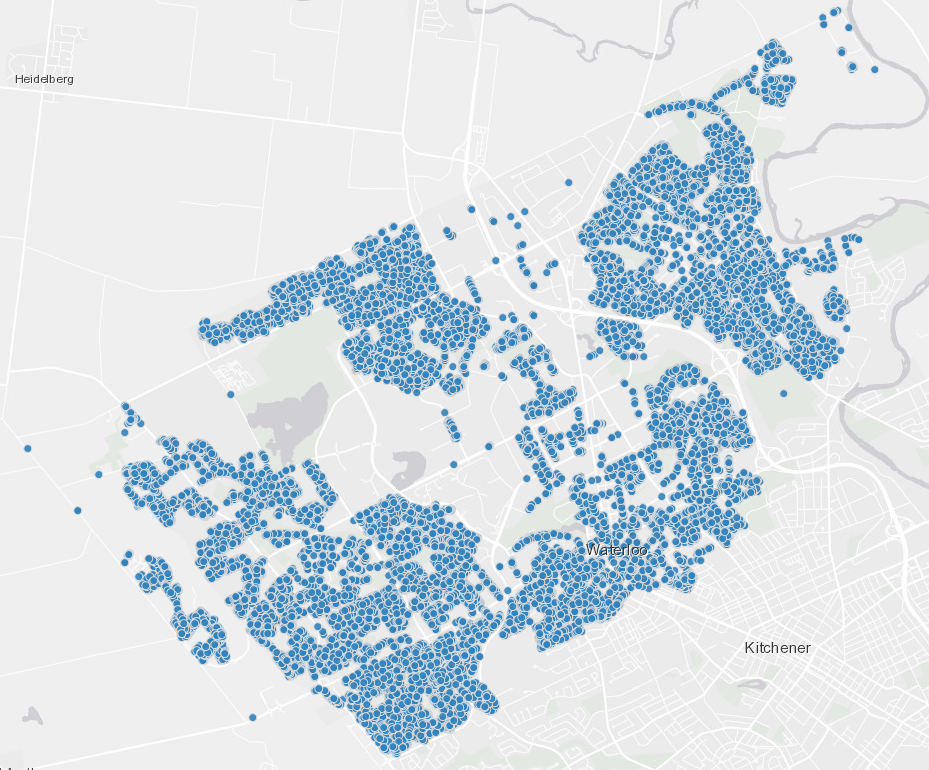

Clojure Books in the Toronto Public Library

Once Upon a Time in Russia

FHIR: A Standard For Healthcare Data Interoperability

First Release of CSVSource

Astonishing Carl Sagan's Predictions Published in 1995

Making a Configurable Go App

Dealing With Pressure Outside of the Workplace

Reacting to File Changes Using the Observer Design Pattern in Go

Provisioning Azure Functions Using Terraform

Taking Advantage of the Adapter Design Pattern

Applying The Adapter Design Pattern To Decouple Libraries From Go Apps

Using Goroutines to Search Prices in Parallel

Applying the Strategy Pattern to Get Prices from Different Sources in Go