Rethinking Software Documentation

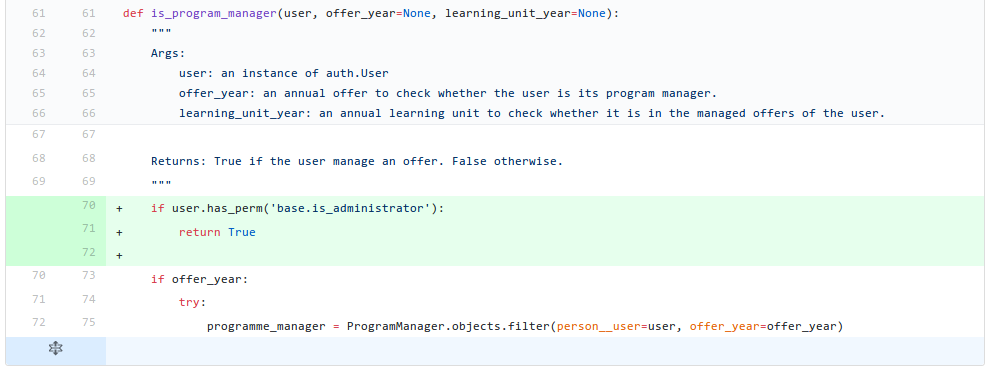

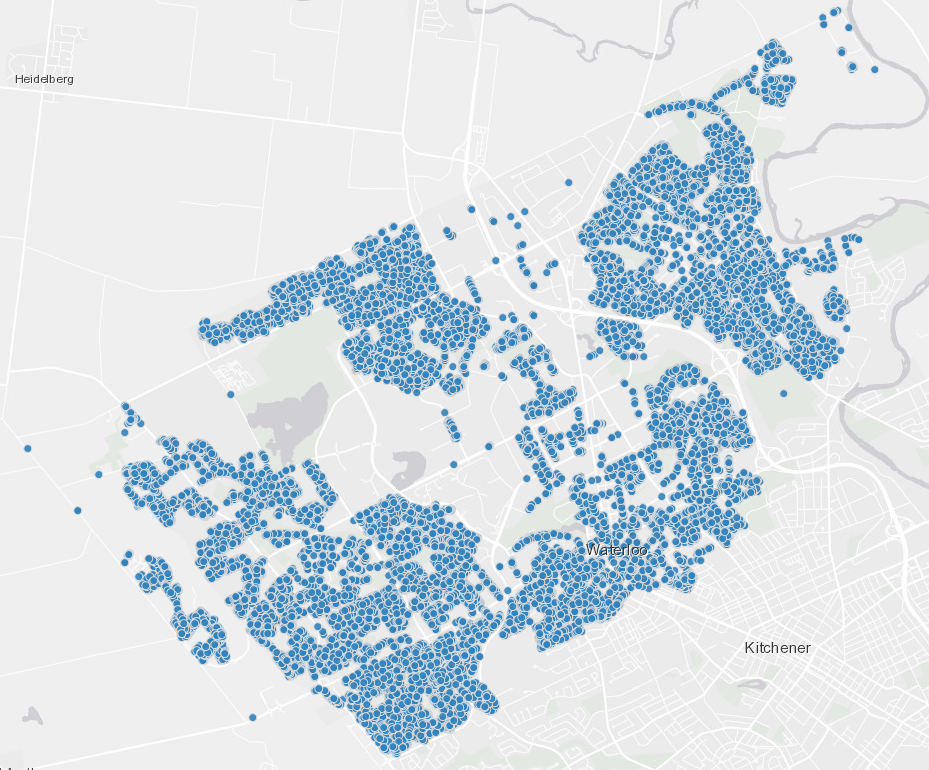

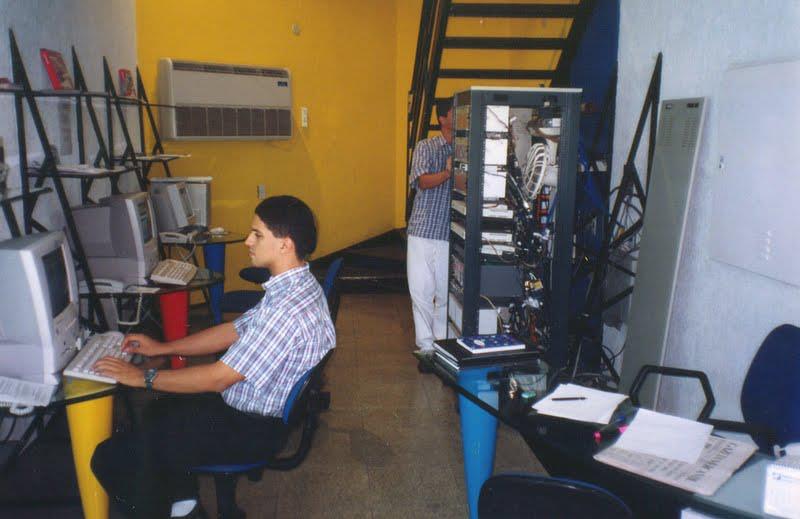

I was reviewing a pull request when I caught an inconsistency

between a code snippet and its documentation. The image below shows a new return

case added to the function is_program_manager, but the developer didn’t update

the documentation accordingly. So, the text still explains the previous return

logic.

Can the developer be held accountable for this omission even when the code runs as expected and passes all tests? In the role of code reviewer I understood that the names used to identify functions and variables were sufficiently clear to make the code readable. No documentation was actually needed. So, I didn’t ask the programmer to fix the documentation. It would mean an additional overhead to the code reviewing process for something that doesn’t cause compilation neither runtime errors.

On the other hand, there are some cases where it’s difficult to represent the business into code. As an example, we have an algorithm that assigns students to internships based on their individual constraints. The documentation is necessary because the code is not trivial.

Code documentation is sometimes useful, but it comes too late, when the code is already written. There is another kind of documentation that comes first: the specification. This term makes people scary these days because it is associated with old fashion software processes, but it is just another name for use cases, user stories, and other fancy synonyms created recently. The point is: The documentation written earlier is a guidance to write code that effectively serves the real intent, minimizing the frustration of developing something that isn’t useful for the users.

Misunderstanding Agility

In the winter of 2001, seventeen people met in a ski resort in Utah to try to find a common ground for software development. They came up with the agile manifesto. The extracted statement below is particulary interesting for the purpose of this post:

“Working software over comprehensive documentation.”

As every philosophical text, this statement is also subject to antagonic interpretations. In my understanding, early documentation doesn’t have to be comprehensive. Done iteratively, it may initially have just enough content to enable a minimal viable product and then progressively covering more and more features as the project advances.

However, in recent talks to some consultants, I realized they interpreted “comprehensive documentation” as a problem to be solved with “no documentation at all”. The disseminated approach is to be limited by post-its or index cards in an informal language description. Once they are implemented, they can be completely discarded, no strings attached. The documentation is transient and summarized in a few sentences. If not registered in an issue tracker, they are lost forever.

That’s sad. Discarding real useful work disturbs me. Unless the users change their minds about the requirements, a major architectural flaw is discovered, or something can be substantially improved, there is no reason to throw something away that frequently. This is waste and every industry avoids it. People’s work must be constructive, the results must be useful and valuable. But how can this principle be applied on software development?

Actually, requirements have been often discarded since the waterfall age. It wasn’t discarded in the sense of throwing away, but in the sense of abandonment. Architecture documents, use case specifications, project guidelines, deployment models, they were created but seldom updated. It was very expensive to keep documentation and implementation synchronized. Aparently, this problem hasn’t been solved yet by any agile methodology. There is indeed an opportunity of rethinking - not reinventing - how documentation should be produced to achieve durability and real added value.

The User Manual

I have been exposed to the inspiring blog post of Tom Preston-Werner: “Readme Driven Development”. For him, it doesn’t matter if you follow TDD, BDD, XP or SCRUM, because at the end “a perfect implementation of the wrong specification is worthless”. He suggests to write the README file first as an essential condition to write good software. We share a fundamental belief that when documenting, we are giving ourselves “a chance to think through the project without the overhead of having to change code every time we change our minds”. Tom is the co-founder of GitHub. So, it isn’t strange that README files play an important role in the presentation of GitHub projects. However, a README file is not designed to grow as the application grows because the entire content is put in a single file. We should limit its content to the point where it is still readable and practical.

The problem with detailed documentation in general is the lack of readers. With a boring writing style and only a few people as audience, a document will hardly be updated as frequently as needed. As the software evolves, only verbal, visual (mock-ups, diagrams, templates, etc.) and short textual communication (emails, issue trackers) prevail. The rest remains forgotten into dusty folders.

We should rethink documentation to become something that people actually read, enjoy, learn and share. Where errors and obsolescence are considered as serious as bugs in software. It happens that documentation might be the primary reason of software success. Classical examples are programming languages, frameworks and platforms (software to build software) where the more documentation is available the higher is the probability of adoption. Not so long ago, we decided to adopt Django for business applications because of its extensive documentation, which helps to reduce the learning curve. On the other hand, my great passion for Clojure has been faded out because of too many gaps in its documentation. Taking this for our apps, a good documentation might be a key success factor.

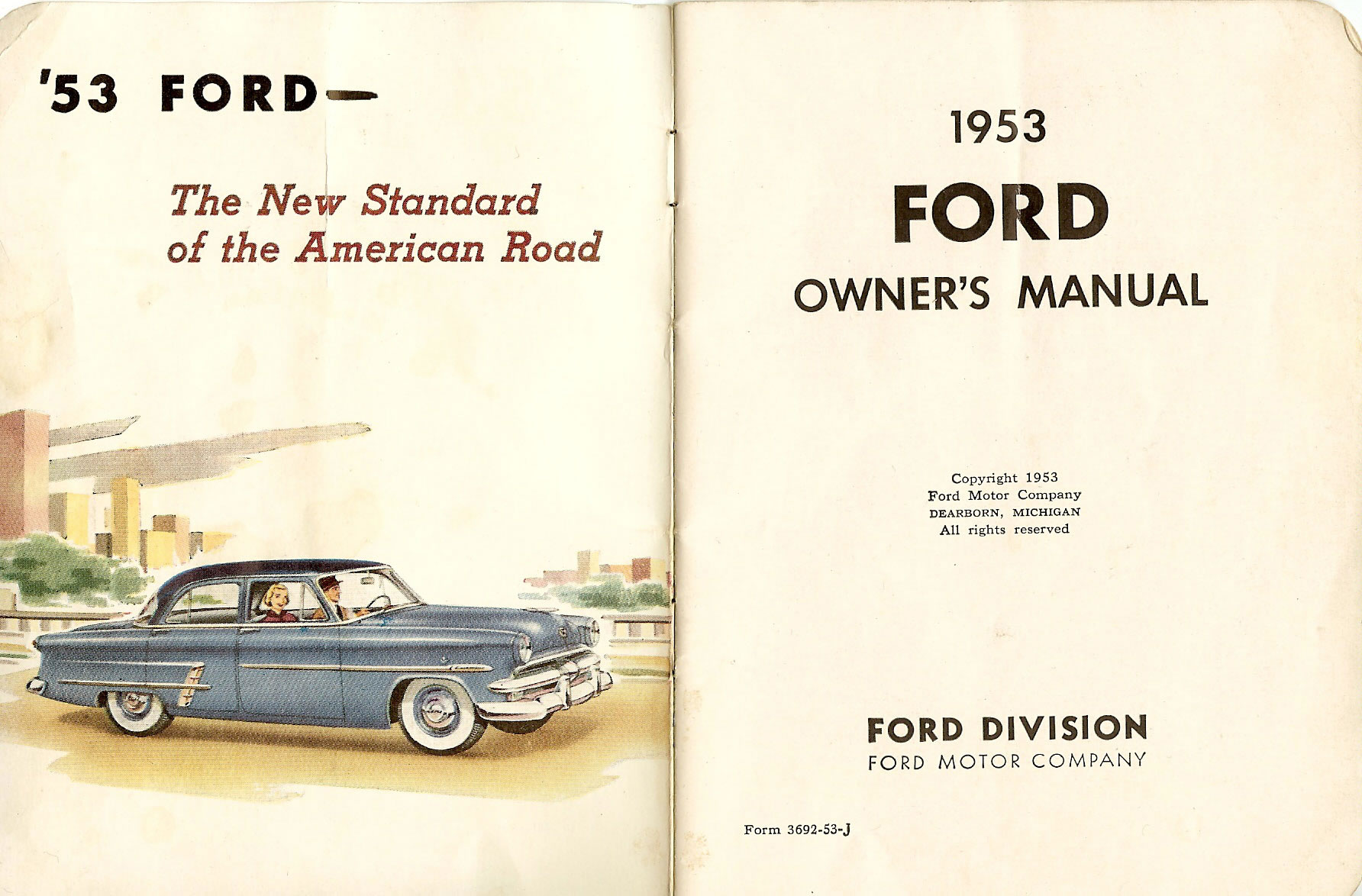

My answer to an effective documentation is to write it in the format of a user manual. In contrast, as the sense of usability grows with good UI practices supported by modern frameworks, the idea of writing a user manual seems to be absurd, until the user asks for one. Take your car as an example. You are so used to drive cars that when you took your current one for the first time, it just happened naturally. You didn’t even touch the owner’s manual. But in the event of the engine’s red indicator lighting up, guess what comes first in your mind? Yes, that heavy manual. You want to know the implications of continuing driving with that light on and how much time you have before sending the car to maintenance.

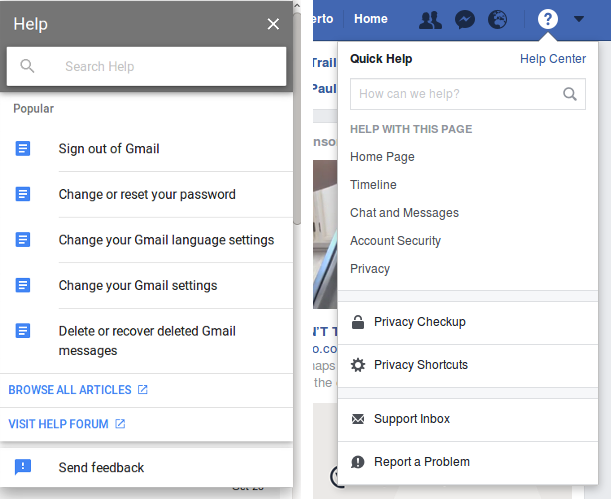

You may say cars are different, old fashioned stuff, that it isn’t the same as software. Well, not really. What your browser, your favorite text editor, Gmail, Facebook and Google have in common ? They all have a help system, which is just another name for user manual. You never noticed it until Facebook changed its privacy rules or you wanted to delete searches & other activities from your Google account. The fact that your users aren’t getting the same from your applications may explain why they aren’t so happy using it.

The user manual is the most valuable documentation - if not the only one - you can write for your application. These are the main reasons why:

-

The text is not disposable because it has too many readers, or potential readers, that will demand it to be up to date.

-

Writing a user oriented document will push you to think more about the user experience and develop better user interfaces.

-

If written at the beginning as a way to elicit requirements, it will be also read by analysts, programmers, support analysts, project managers, product owners, and real users.

-

Everybody around a single document, providing feedback, makes it continuously improved and updated.

-

A user manual is the best guide to write automated functional tests. When all tests pass then the user manual is also correct.

Writing is a thinking exercise. If you want to think a lot about a subject, write about it. The more you think the more consistent the idea will become. I started drafting the text you are reading right now about three months ago. Every time I visited it I rephrased something, replaced paragraphs by entirely new ones, and changed the title countless times. The more I think the higher is the chance of getting it right, but I had to stop at some point so I could release it. The minute after the release, as I kept thinking and re-reading it, a word, a phrase or a paragraph became obsolete. Better thoughts may be published in a future post if I insist on the subject.

Now, consider that the subject is software. Writing about it will make you think a lot and be careful about its consistency. You don’t have to write everything at first, but you can do just enough to move forward. If you don’t write anything, you will forget details, consistency is never stable, everything remains in the head of people directly involved, but for a short period of time. Every time you have to explain something you have to remember everything. Instead of writing several different documents, you can write a single one: the user manual, which is useful for everybody. Consequently, you will have several readers who will help you to think about the same software, over and over again, without even bothering you.

I’ve been busy maintaining a software that was considered more problematic than useful. They considered rewriting it several times. When I accepted the challenge I intuitively asked for any documentation available. Found nothing I could rely on. I spent several days reading the code to understand it. I wrote down every understanding I extracted from the code. The text evolved into a user manual, useful for myself and for anybody else who might get the project after me. (S)he will need just a few hours to understand the whole picture and move on from where I stopped. I hope that person reads this post and gets conscious of the importance of maintaining the user manual the same way code is maintained.

Recent Posts

Can We Trust Marathon Pacers?

Introducing LibRunner

Clojure Books in the Toronto Public Library

Once Upon a Time in Russia

FHIR: A Standard For Healthcare Data Interoperability

First Release of CSVSource

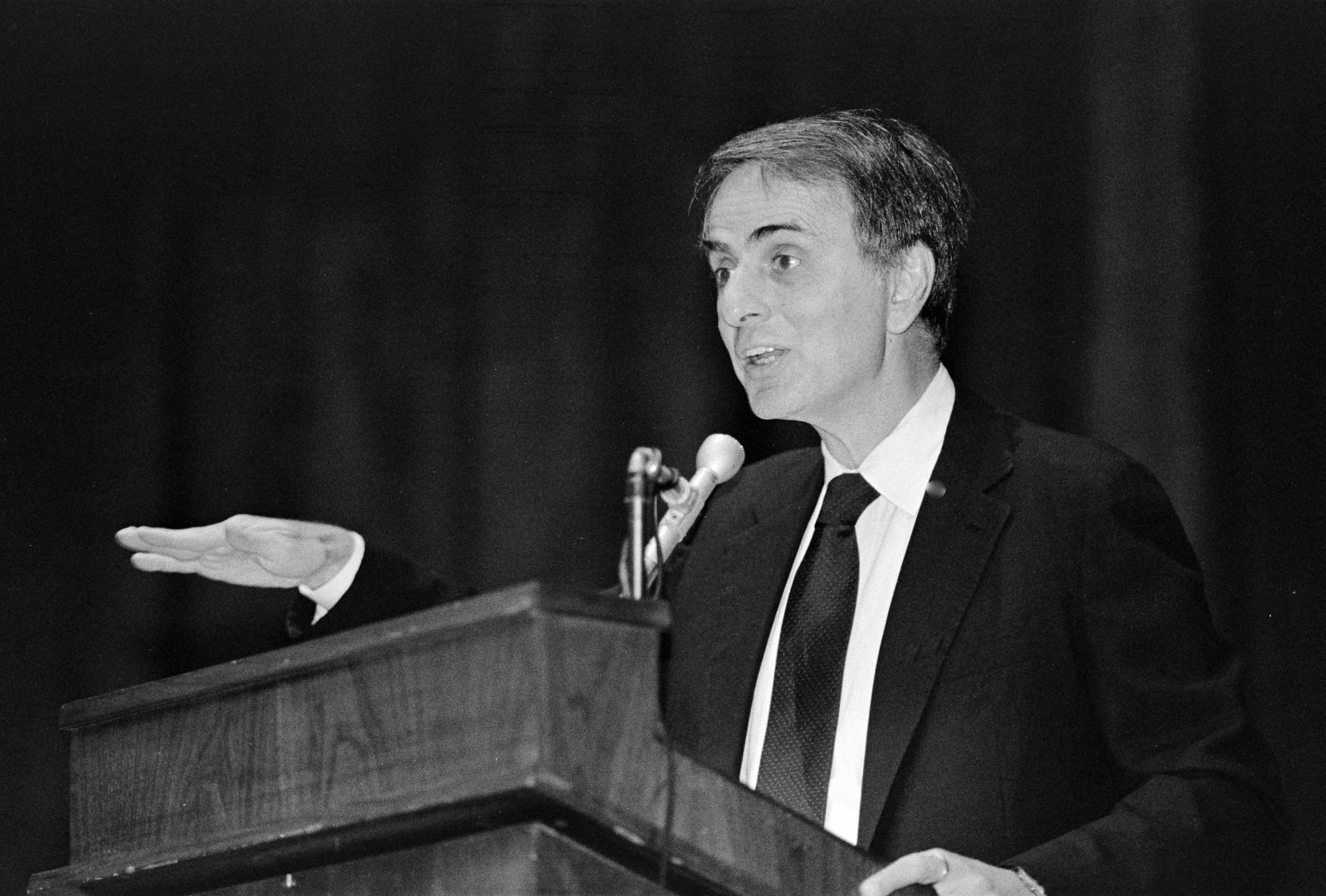

Astonishing Carl Sagan's Predictions Published in 1995

Making a Configurable Go App

Dealing With Pressure Outside of the Workplace

Reacting to File Changes Using the Observer Design Pattern in Go

Provisioning Azure Functions Using Terraform

Taking Advantage of the Adapter Design Pattern

Applying The Adapter Design Pattern To Decouple Libraries From Go Apps

Using Goroutines to Search Prices in Parallel

Applying the Strategy Pattern to Get Prices from Different Sources in Go